Signe Bendsen has a MSc in physics from NBI, University of Copenhagen, and is currently a Research Scientist at Liva Healthcare. She recently defended her thesis titled: “Revisiting the Gender Representation Disparities in Physics from 1970 to 2023”. The thesis can be found here

Congratulations on obtaining your MSc! What was your motivation to study physics in the first place?

Thank you so much! My motivation to study physics stemmed from a blend of personal exploration and practical considerations. Initially, I pursued a creative path in dance and music, even moving to Paris to chase a dance career. However, after a year, I realized it wasn’t the right fit for me. The dance industry exposed me to a tough working culture, where opportunities were often low-paid or unpaid. While I did grieve giving up on dancing, this experience also made me realize that I value stability and fair compensation in a career.

Forced to reconsider what truly interested me beyond the arts, I remembered my passion for natural sciences and how I excelled in them during school. This made me consider biology, physics, and mathematics. Physics stood out because of its interdisciplinary nature, bridging hardcore disciplines like math and statistics with philosophical and ethical questions about life and existence. It also offered a broad range of skills, such as statistics and programming, which would open many doors in the industry, especially when combined with fields like biology. Ultimately, choosing physics was a balance of practicality—seeking a stable, well-compensated career—and nurturing my intellect and curiosity about the natural world and its deeper questions.

How did you come up with the idea to write about gender bias in scientific publishing for your thesis? And how was the idea received by your supervisors?

The idea to write about gender bias in scientific publishing (within physics) for my thesis had been brewing inside me for most of my studies. I was fascinated by the history of the Niels Bohr Institute, where I often studied, soaking in the century-old atmosphere. As I wandered the halls, I became curious about the women in the photos on the walls—women whose contributions seemed overshadowed by their male counterparts. This observation sparked my awareness of gender and identity bias, which only grew stronger throughout my time as a physics student.

By the time I started my master and started to think about a thesis topic, I didn’t really believe that the institute would accept to write about something so untraditionally physics as gender bias. Therefore, I explored various options with potential supervisors. However, none of it really ignited my passion – the only subject that truly resonated with me was the issue of gender bias. As the thesis topic deadline approached, I felt desperate that I still hadn’t found anything that truly resonated with me and so I realized I had to stick to my gut and go with the idea about gender bias. So, in the end I decided to speak up and ask my supervisors to let me write about this – even though I was scared that they would consider my idea dumb or impossible.

My supervisors were initially supportive but cautious, as the topic was outside their usual expertise. I had to push them to take on the project, but they got on board once they saw my commitment and the team I had assembled. I brought together four supervisors with different skills: Mathias Spliid and Troels Petersen from NBI, who guided me in data analysis, statistics, and machine learning; Mathias Wullum from Sociology, who provided expertise in this type of analysis; and Martina Erlemann from Freie University Berlin, who specializes in gender bias in physics and offered feedback through a research seminar.

I don’t think they fully understood my vision, so it was a bit of a risk – but I knew exactly where I wanted to go with the project and so as soon as I got their acceptance, I was very happy and relieved! And so, they got on board and ended up being very supportive and eventually, I think they even enjoyed the challenge of guiding me through this unconventional but important project 😉.

What are the 5 most important takeaways from your thesis?

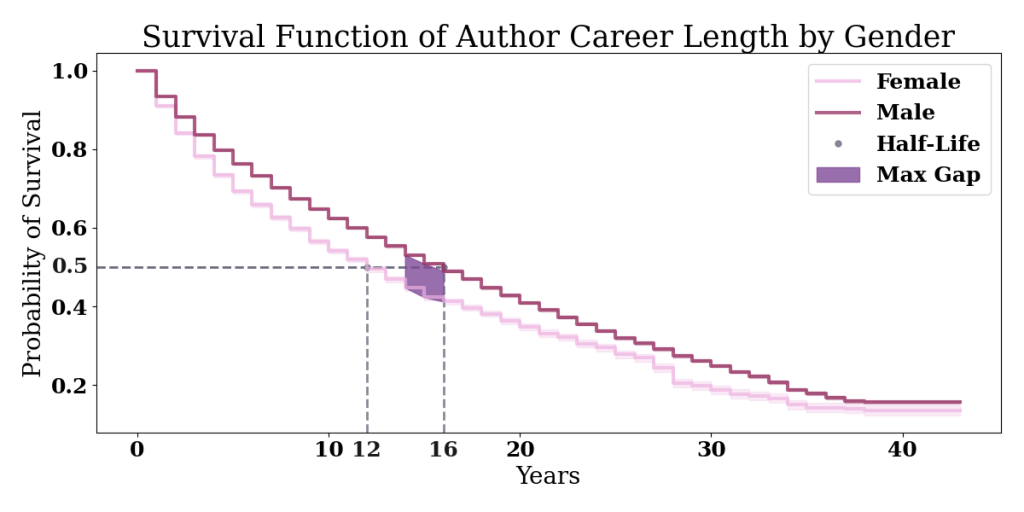

- I think the main takeaway from my thesis is the “survival curve” which shows that female researchers are more likely to “drop out” of their academic careers than their male counterparts, a trend that persists throughout their careers. Even after investing significant time and effort—completing a PhD, postdoc, and beyond—female researchers have a shorter “career half-life” (12 years) compared to male researchers (16 years). I think this finding is particularly interesting because it challenges the common argument that “women are simply less interested in STEM.” The survival analysis demonstrates that these women have already shown sustained interest and dedication-completing a masters, PhD, postdoc, and beyond. Despite this, they still face greater obstacles in maintaining their careers compared to their male colleagues. I think this is a huge indicator that the gender disparities that we see within physics and STEM go way beyond whether someone of a specific gender is “interested” in the field or not but rather that we are dealing with systemic issues within the field that hinder women’s long-term success and recognition.

- Moreover, I found that there is a statistically significant gender disparity in publication-related variables, particularly in citations and prestige. However, one of the only variables that were not significantly smaller for female authors was the number of publications per year: this was significantly larger! Female authors, despite on average producing more publications per year than their male colleagues, receive less recognition and prestige. This indicates that the contributions of women in physics are undervalued, affecting their visibility and career advancement.

- While there has been an increase in the number of publications by female authors in physics from 1970 to today (increased by 9%), a logistic projection on this trend suggests that gender parity (50% female authorship) won’t be reached until the year 2170— this is 146 years from now! This slow progress highlights the need for dedicated efforts to change the current culture within physics, as the existing trajectory will not achieve gender balance in a timely manner. This is particularly concerning given institutional goals (without an exact strategy on how to achieve them), such as the Niels Bohr Institute’s aim to reach 30% female professors by 2030.

- I also found it interesting that there are notable variations in gender distribution across different subfields of physics, which seem to align with traditional gender roles. For example, women are more represented in fields like Medical Physics and Didactic Physics, which are (according to theories within sociology) traditionally associated with female roles in health and education (nurturing and caretaking). In contrast, subfields such as Particle Physics, Machine Learning, Computational Physics, and Quantum Physics are heavily male-dominated, reflecting traditional associations between men and technology – the more entanglement between men and machines the

more masculine the field is considered traditionally.

- Another interesting finding regarding subfields was that female authors are generally more represented in fields of higher prestige level. However, it is still the male authors in that field dominating in driving the rankings and recognition. This suggests that even within more “favorable” subfields, female researchers are still not receiving equitable recognition, further illustrating the pervasive nature of gender bias in scientific publishing within physics.

Your conclusions are based on results from statistics and Machine Learning methods, can you elaborate on which models you utilize and how?

I analyzed a very large dataset which contained info on more than a million publications within physics from 1970 to 2023.

However, the data didn’t include any information on the author’s gender nor the physics subfield, so I had to extract those variables first of all. I started by extracting the gender variable using a gender API, which identified gender based on names and country of origin (which was included in the original dataset). I also used a Topics Model to determine the subfield of each publication by clustering the words in the abstract based on Bayesian statistics, grouping them according to common themes.

I applied various statistical tests like the chi-square contingency test, t-test, and U-test to check for significant differences between genders for each variable. For example, the chi-square test helped me explore relationships between gender and categorical variables, while the t-test and U-test were used to compare continuous variables like citation counts or career duration.

Additionally, I used Machine Learning models to predict gender based on other variables in the dataset. I used UMAP for cluster analysis, which helped me visualize patterns in the data, and LightGBM for classification to see how well the model could predict gender using the available variables.

Do you have any plans to continue the work from your thesis?

Yes, in some way. While my thesis focused on quantitative methods, I’d love to dig deeper into the lived experiences behind these numbers and results. I’m interested in exploring these findings through more qualitative or historical research, and perhaps turning it into something more accessible, like a book or a piece of popular culture, rather than just a scientific paper.

Initially, after submitting my thesis, I needed a break from it, and I wasn’t sure about continuing the work in its current format. But now that I’ve had some distance, I’m considering getting parts of it published or sharing the data I generated. It wasn’t in my original plans, but as I take a step back, I might change my mind.

What kind of initiatives would have made it easier for you as a woman to get interested in physics? Or supporting you through your physics degree?

This is an excellent but challenging question! Overall, I think that I often felt overlooked as someone who could pursue a career in physics or science, despite consistently achieving good grades. I faced assumptions based on my appearance and demeanor—being short, blonde, and very girly—leading some to doubt my intellectual abilities or suggest I should pursue something more traditionally feminine. I did, however, have a few people in my life, who actually recognized these skills in me, and I am not sure I would have realized it myself if it wasn’t for them. It took me a long time to identify as a physicist, and I’m still working on fully embracing that identity.

To address these issues, I believe we need to move away from stereotypical identities associated with specific fields of study. Physics, in particular, often romanticizes a certain profile—an introverted, male genius reminiscent of Niels Bohr or Einstein. This narrow view can obscure many potential talents and discourage diverse individuals from pursuing physics. I think talent and identity recognition-despite gender, or other appearance would have made my journey much easier.

Educational institutions, including universities, have a significant role in challenging these stereotypes. They should be mindful of how they communicate and present their programs, ensuring that they are inclusive and welcoming to all students. For instance, ITU has made notable efforts to describe and teach its programs in ways that are more inclusive of minorities, especially women. Lots of literature and research on how to do so exists, so there is no excuse but to start employing it.

Additionally, I think that increasing awareness of the history of women in physics is crucial. While most historically recognized physicists are male, it’s important to understand that this is not due to some natural law of physics. There is an underlying explanation for that. Women were excluded from universities until late 1800. Women, still being viewed as primary caretakers (or as a man’s property), faced significant barriers to education and professional opportunities. Furthermore, many contributions by women were overlooked or misattributed. By incorporating this historical context into the curriculum at institutions like NBI, we can help women (and other minorities) see their place in the physics community and recognize the legacy they are part of. I think experiencing a focus on this would have felt more inclusive and less isolating.

You are now employed full-time as a Research Scientist at Liva Healthcare, can you give us a description of the work you do in your position?

Yes, I work in the research department of Liva Healthcare as a Research Scientist. I generate the evidence and research that underpin the company’s initiatives. My role involves generating research ideas, analyzing data, creating plots, and writing scientific papers. I also prepare presentations and deliver oral talks at conferences focused on digital medicine and diabetes. Additionally, the research I conduct supports both the marketing and sales efforts of the company, helping to showcase our innovations and findings.

What made you decide to pursue a career in the private industry?

Initially, I envisioned a career as a researcher in biophysics, but over time, my needs and interests changed. Going back to the way I felt about dancing, academia (and being a student) is a very tough working environment and so I really wanted to explore the benefits and stability of the private industry.

In the medtech sector, I’m able to apply my knowledge and interests in human health and technology without the constraints I found in academia. The private industry offers a fast-paced environment where the impact of your work is more immediate and visible. The private sector also provides a more tangible connection to real-world applications. I would also sometimes feel quite introverted and isolated in academia whereas the private industry offers much more social interactions, teamwork, and collaboration, which I needed at this point of my life. Overall, I felt this way of working was more fit for my current temper, ambitions, and interests – I am not saying that I will never go back to academia, but I am very happy in the private industry for now!

How do you use the skills you learned as a physicist in your work?

I think the key skill that you learn as a physicist is problem-solving. You learn to deal with very abstract ideas and break them down into sub-problems that can actually be solved – a method that’s incredibly useful for basically any task. This approach helps me maintain a clear structure and efficient workflow, which is essential in the fast-paced private industry.

In addition to problem-solving, I apply my skills in statistics, biology/medicine, programming, and machine learning. My background in physics also enhances my ability to gather and analyze knowledge, mediate discussions, and communicate findings effectively, both in writing and orally. These skills are crucial for addressing complex issues and presenting solutions in a clear and impactful way.

What advice would you give to young people (in particular women and minorities) with a background in physics who would like to pursue a career in the private industry?

Well, the advice is simply: Just apply! The only job you’re sure not to get is the one you didn’t apply for. Even if you don’t land the job, applying can provide valuable feedback on your application and interview.

That being said, here are my best tips:

- Get Your Foot in the Door: While there are many positions available for physics graduates (and students), there’s also competition. The private industry values work experience, so getting that first opportunity is crucial. If you can’t find relevant jobs, try applying through your university. You can do your bachelor’s or master’s project with a company or use your “projekt udenfor kursusregi” (PUK) to work on a project with a company. Many companies are open to this as it gives them free work, while you gain experience and start building your network and resume.

- Polish Your Resume and Application: Make sure your resume and application reflect your personal style while staying professional. Use free templates for inspiration and get feedback from your network, student associations, union (fagforening), or career consultants at your university. These resources are free while you’re a student, so make the most of them!

- Find Role Models: Look for role models or companies that align with your career goals. Follow them on LinkedIn or other social media to stay updated on the industry and find inspiration. LinkedIn is also great for job postings. Investigate the backgrounds of your role models to understand their paths to success. I think role models are especially important for women and minorities, as they show that success is possible and validate your own path, even if it sometimes feels like you’re alone.

- Explore and Learn: Try different courses to better understand yourself, your work style, and your career aspirations. Consider how what you learn at university applies to the industry. Stay curious, keep learning new skills, and explore different career options. It’s okay if your interests and goals evolve over time—what matters is continuing to move forward.

- As a minority: Lastly – take advantage of your position as a minority! Your unique background might be exactly what makes you stand out and bring a different viewpoint that can be valuable to employers – use this to your advantage!